The Short (and Slightly Immature) Answer

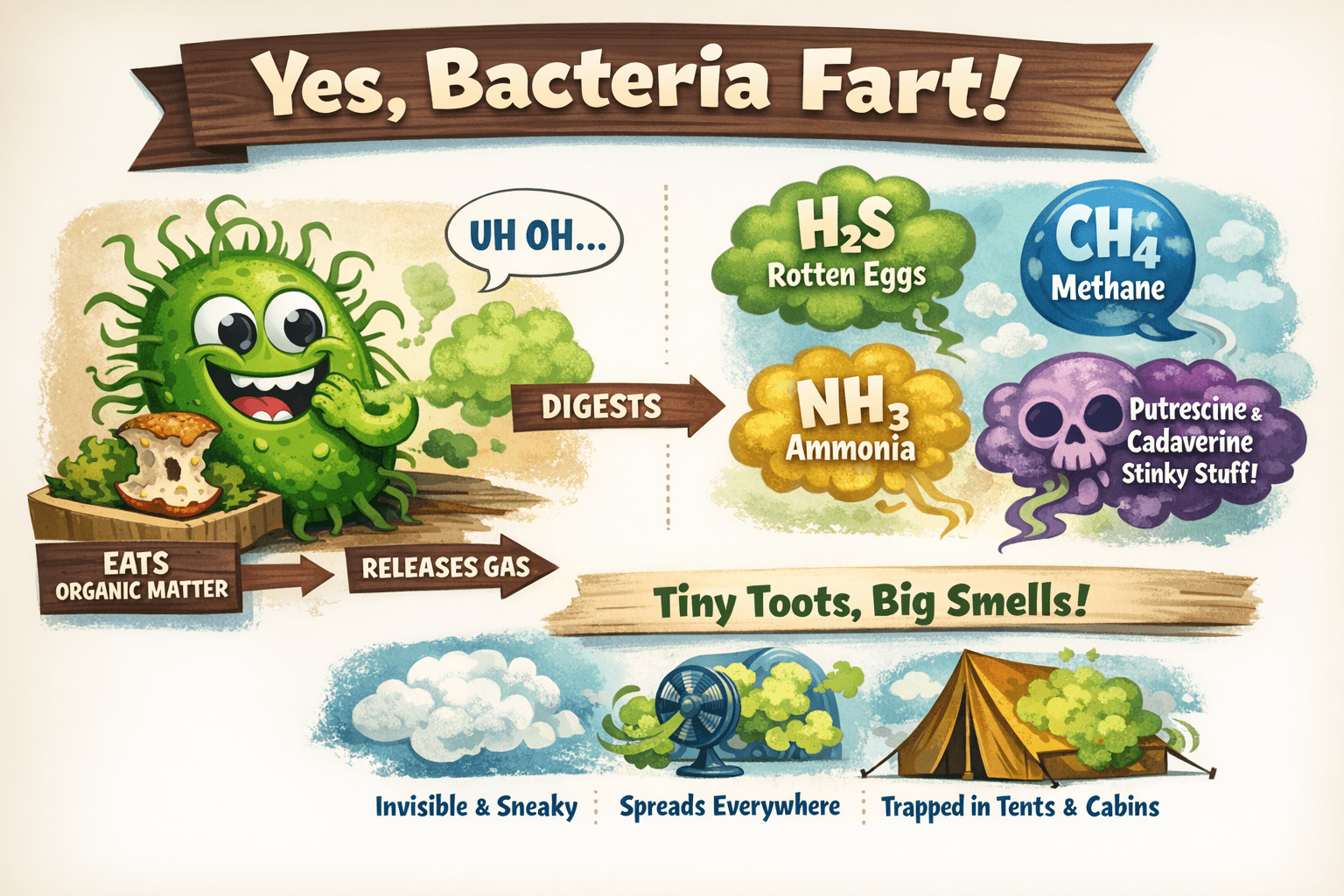

Yes—bacteria fart.

They don’t wear pants, they don’t feel embarrassed, and they definitely don’t say “excuse me,” but when microbes consume organic matter, gas is often the unavoidable byproduct. Those gases are responsible for many of the smells we associate with rot, spoilage, mildew, sewage, body odor, pet odor, and even that unmistakable closed-up camp smell.

The longer answer is more interesting—and surprisingly useful when you’re trying to control odor instead of just covering it up.

What Bacteria Actually Do for a Living

Bacteria survive by breaking down organic material. That material can include:

- Food scraps

- Sweat and skin oils

- Pet dander and waste

- Dead insects

- Mold spores

- Plant material

- Body waste (human or animal)

In simple terms, bacteria eat complex organic molecules and digest them into smaller ones. During this metabolic process, gases are released, just like in larger animals.

Different bacteria + different food sources = different gases.

And that’s where odor begins.

The Microbial Gas Menu (Yes, It’s a Thing)

Here’s where the science gets fun—and a little gross.

Common Gases Produced by Bacteria

- Hydrogen sulfide (H₂S)

Smells like rotten eggs. Often produced when bacteria digest sulfur-containing proteins. - Ammonia (NH₃)

Sharp, acrid odor commonly associated with urine, sweat, and animal waste. - Methane (CH₄)

Odorless on its own, but usually accompanies other foul-smelling gases. Famous for its role in farts and swamps. - Putrescine & cadaverine

Byproducts of protein decay. Yes, they are literally named after rotting flesh—and yes, they smell exactly like you’d expect. - Volatile fatty acids (VFAs)

Sour, rancid, or cheesy odors common in spoiled food and body odor.

Each gas is invisible, lightweight, and mobile—perfect for spreading throughout enclosed spaces like tents, cabins, RVs, boats, and storage bins.

Why Odors Are Worse in Closed or Damp Spaces

Bacteria thrive when four conditions overlap:

- Food (organic residue)

- Moisture

- Warmth

- Time

That’s why odors explode in:

- Packed tents

- Sleeping bags

- Boots

- Coolers

- Cabins closed for the season

- Boats and RVs in storage

Once bacteria get comfortable, the gas production ramps up—and since gases don’t politely stay put, the smell spreads far beyond the original source.

Why Covering Odor Doesn’t Work (and Sometimes Makes It Worse)

Air fresheners, perfumes, and scented cleaners don’t stop bacteria from eating.

At best, they temporarily mask the smell. At worst, they add new organic compounds for bacteria to consume—leading to even more gas later.

It’s the microbial equivalent of spraying cologne on a gym bag.

The bag is still gross.

The Only Real Way to Stop the Smell: Interrupt the Biology

Odor control only works when you address one (or more) of the following:

- Remove the food source

- Kill or deactivate the bacteria

- Change the chemistry so gas can’t form

- Neutralize the gases after they’re produced

This is why oxidizing technologies—like chlorine dioxide (ClO₂)—are so effective.

Instead of masking odor, they:

- Disrupt bacterial metabolism

- Break down odor-causing gases at the molecular level

- Prevent new gas formation without leaving residue

In other words: no bacteria dinner, no bacterial fart.

Why This Matters for Camping, Storage, and Everyday Life

Once you understand that odors are gases produced by microbes, everything changes:

- That “wet tent smell” isn’t fabric—it’s bacteria dining on moisture and dirt

- Foot odor isn’t feet—it’s microbes digesting sweat

- Pet odor isn’t the pet—it’s bacteria processing dander and oils

- Cabin stink isn’t the wood—it’s microbial gas trapped indoors

Stop the microbes, and the odor stops with them.

Final Thought (Yes, We’re Going There)

People laugh about farts because they’re human.

But the truth is, most of the worst smells in your environment aren’t human at all—they’re microbial.

And once you understand how bacteria fart, you’re finally equipped to stop them.

Which is, frankly, a breath of fresh air.

Clear, Direct Answer

Yes—bacteria do produce gas when they consume organic matter, and those gases are the true source of most persistent odors in tents, cabins, RVs, boats, gear, pets, and people. Framing odor as microbial flatulence is scientifically accurate, memorable, and effective for educating readers on why masking smells fails and why oxidation works.